The photographers are being photographed. Robert Mapplethorpe will soon be dead, but today he basks in the role of subject rather than artist. Norman Parkinson joins him, supremely tall and regal, with signature beanie on his head. The beanie is a Kashmiri wedding hat, one he has worn through decades of photographing the royalty of England and the royalty of fashion.

Behind the camera is Annie Liebovitz. She is disturbed the advertising people are there. They are an extraneous nuisance, and there are so many of them. She does not suffer fools or most others too easily, apparently. She is even snippy. But the advertising people are there because this is an ad, and the three immortals of the darkroom will have to cope.

Behind the camera is Annie Liebovitz. She is disturbed the advertising people are there. They are an extraneous nuisance, and there are so many of them. She does not suffer fools or most others too easily, apparently. She is even snippy. But the advertising people are there because this is an ad, and the three immortals of the darkroom will have to cope.

I try to put her at ease. I say something nice about the rear end of Bruce Springsteen. She has just shot the cover for Born in the USA and the proofs lie on the table. The Boss stands with back to camera in iconic white T-shirt and jeans and red truckers cap jutting from his pocket, set against the red and white stripes of some humongous American flag. It is all icon all the time. “We didn’t really get the shot,” Annie mumbles. It seems more a knee-jerk response to flattery than the photographic truth about Bruce Springsteen’s rear end. She would be intimidating even if she didn’t wish I wasn’t there. Enormously tall, in white jumpsuit and special grey plastic glasses, she is not a woman so much as a mechanic of seeing.

The mission that has brought us here is advertising’s eternal mission: re-enchantment. The product is a stodgy old liquid squeezed from limes: Rose’s Lime Juice. Who would guess a British lime juice of almost negligible interest would become a vehicle for a sea of meanings?

The tagline of Roses is The Uncommon Denominator. The target of the campaign is the avant garde art and gay communities. It is an old mixer for new drinks, so the campaign mixes two cultural celebrities, one old and one new. One established and one avant garde, One Parkinson and one Mapplethorpe.

I tell Robert I read an essay about his work in a magazine and couldn’t understand a word of it. “The ouvre of Robert Mapplethorpe reflects an is-ness and not-isness where the shifting visual field recapitulates the identity, where the forbidden counterposes itself with the permissible, and subject and field reverse themselves.” This is not what the article said at all. It’s not even close to what it said. But this is my impersonation of my memory of what the article said. Robert pauses, surprised I would even want to understand it. “It did its job,” he says, laconically. That is all he says.

“It did its job.” That said it all. It was about career, not art. Or, art was a career. Or, career was art. Whatever the case, the job of the essay was simply to be there, to represent “scholarly article,” rather than to actually be a scholarly article. Maybe the writer didn’t even understand it. The article was an artifact of meaning, not an evaluation of photography. The existence of the article signified Robert Mapplethorpe was an artist of a certain stature, with all the rights and profits accruing to an artist of that stature. Period. Reading over.

It is like the business books handed around by executives who write them (or have someone write it for them.) The mere existence of a book conveys a meaning and a stature, and the last thing that is expected of you is to read it. It is there to mean, and that is enough. It did its job.

Mapplethorpe is handsome, swaggering. A rock star in the older sense of the word, more like James Dean than what rock stars eventually became. He is ineffably cool. But he is sick, and not long after the shoot, it is announced he has AIDS.

For marketers, the challenge of a personality-based campaign is that it rises and falls on the back of a personality. It is not likely that anytime soon, a copywriter working on Hertz will walk into his creative director’s office and suggest: “Hey, why don’t we bring back OJ?”

The Roses Lime Juice client faced the cruel, almost unspeakable decision of associating her brand or not with someone tragically passing from disease, a tainted disease at that particular point in time. It is cruel, but that’s what marketing people discuss in the privacy of their office. Mapplethorpe’s ambition, his careering, his prolific output and classical renderings of rather un-classical subjects, from almost pornographic close-ups of flowers to actual pornographic renderings of a bull whip up the ass, made him an artist of stature. But inhabiting the gay S & M demimonde of the 1980’s made him an almost inevitable victim of his generation’s plague.

In the Annie Liebovitz photograph selected for the ad, Robert Mapplethorpe and Norman Parkinson pose by a white human statue against the quaintly artificial backdrop of a Nineteenth Century garden. Another mix: a contemporary photographer’s wink to an old photographic tradition. The client eventually decided to run the ad and nobody’s life was changed by it, not the photographers’, not the ad people, and not the Roses Lime Juice people.

I saw Robert for the last time at the Robert Miller Gallery on 57th Street. It was his final opening. The rock star swagger was gone. The virus had ravaged his body. He shuffled slowly in the velvet monogrammed bedroom slippers of a prince, supporting himself on a pearl-topped cane. I wondered if he wore his disease as a final artistic flaunt to his Catholic childhood in Our Lady of the Snows Parish in Floral Park, Long Island.

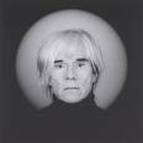

The demimonde from which he had risen taxied uptown to pay their respects. Grace Jones was dressed as a policeman and carried a gun. But the soul of the event seemed to be Andy Warhol, no longer existing in flesh, staring down beatifically in two-dimensions from a photograph on the wall. In the portrait, Mapplethorpe had placed a halo behind Warhol’s face and printed the photograph in a lush silver process on canvas, like a classical painting.

What was the meaning of the deification of the Prince of False? Had Warhol’s artistic celebration of the images of mass production been social commentary? An ironic comment on the debasement of a culture bereft of any meaning save those of commerce? Or was the message of the Campbell’s soup can simply that you don’t need to render Italian landscapes, that if you knew how to look, there was beauty in even our most mundane everyday objects?

Was Robert Mapplethorpe’s final beatification of Andy Warhol yet one more level of meaning added to the artist who epitomized the Marketplace of Meanings?

Or was I thinking too much?

Maybe the photograph was just doing its job.

The mission that has brought us here is advertising’s eternal mission: re-enchantment. The product is a stodgy old liquid squeezed from limes: Rose’s Lime Juice. Who would guess a British lime juice of almost negligible interest would become a vehicle for a sea of meanings?

The tagline of Roses is The Uncommon Denominator. The target of the campaign is the avant garde art and gay communities. It is an old mixer for new drinks, so the campaign mixes two cultural celebrities, one old and one new. One established and one avant garde, One Parkinson and one Mapplethorpe.

I tell Robert I read an essay about his work in a magazine and couldn’t understand a word of it. “The ouvre of Robert Mapplethorpe reflects an is-ness and not-isness where the shifting visual field recapitulates the identity, where the forbidden counterposes itself with the permissible, and subject and field reverse themselves.” This is not what the article said at all. It’s not even close to what it said. But this is my impersonation of my memory of what the article said. Robert pauses, surprised I would even want to understand it. “It did its job,” he says, laconically. That is all he says.

“It did its job.” That said it all. It was about career, not art. Or, art was a career. Or, career was art. Whatever the case, the job of the essay was simply to be there, to represent “scholarly article,” rather than to actually be a scholarly article. Maybe the writer didn’t even understand it. The article was an artifact of meaning, not an evaluation of photography. The existence of the article signified Robert Mapplethorpe was an artist of a certain stature, with all the rights and profits accruing to an artist of that stature. Period. Reading over.

It is like the business books handed around by executives who write them (or have someone write it for them.) The mere existence of a book conveys a meaning and a stature, and the last thing that is expected of you is to read it. It is there to mean, and that is enough. It did its job.

Mapplethorpe is handsome, swaggering. A rock star in the older sense of the word, more like James Dean than what rock stars eventually became. He is ineffably cool. But he is sick, and not long after the shoot, it is announced he has AIDS.

For marketers, the challenge of a personality-based campaign is that it rises and falls on the back of a personality. It is not likely that anytime soon, a copywriter working on Hertz will walk into his creative director’s office and suggest: “Hey, why don’t we bring back OJ?”

The Roses Lime Juice client faced the cruel, almost unspeakable decision of associating her brand or not with someone tragically passing from disease, a tainted disease at that particular point in time. It is cruel, but that’s what marketing people discuss in the privacy of their office. Mapplethorpe’s ambition, his careering, his prolific output and classical renderings of rather un-classical subjects, from almost pornographic close-ups of flowers to actual pornographic renderings of a bull whip up the ass, made him an artist of stature. But inhabiting the gay S & M demimonde of the 1980’s made him an almost inevitable victim of his generation’s plague.

In the Annie Liebovitz photograph selected for the ad, Robert Mapplethorpe and Norman Parkinson pose by a white human statue against the quaintly artificial backdrop of a Nineteenth Century garden. Another mix: a contemporary photographer’s wink to an old photographic tradition. The client eventually decided to run the ad and nobody’s life was changed by it, not the photographers’, not the ad people, and not the Roses Lime Juice people.

I saw Robert for the last time at the Robert Miller Gallery on 57th Street. It was his final opening. The rock star swagger was gone. The virus had ravaged his body. He shuffled slowly in the velvet monogrammed bedroom slippers of a prince, supporting himself on a pearl-topped cane. I wondered if he wore his disease as a final artistic flaunt to his Catholic childhood in Our Lady of the Snows Parish in Floral Park, Long Island.

The demimonde from which he had risen taxied uptown to pay their respects. Grace Jones was dressed as a policeman and carried a gun. But the soul of the event seemed to be Andy Warhol, no longer existing in flesh, staring down beatifically in two-dimensions from a photograph on the wall. In the portrait, Mapplethorpe had placed a halo behind Warhol’s face and printed the photograph in a lush silver process on canvas, like a classical painting.

What was the meaning of the deification of the Prince of False? Had Warhol’s artistic celebration of the images of mass production been social commentary? An ironic comment on the debasement of a culture bereft of any meaning save those of commerce? Or was the message of the Campbell’s soup can simply that you don’t need to render Italian landscapes, that if you knew how to look, there was beauty in even our most mundane everyday objects?

Was Robert Mapplethorpe’s final beatification of Andy Warhol yet one more level of meaning added to the artist who epitomized the Marketplace of Meanings?

Or was I thinking too much?

Maybe the photograph was just doing its job.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed